What do youth and cultural centers, youth hostels and scouting have in common? Each of these movements or associations is linked to what is called popular education, which intends to improve the functioning of society without the support of traditional institutions.

But how can this non-school educational process be defined more precisely? Popular education has a specific history, principles and practices. What does it represent today? How can it be a real political project and innovative education in XXI

th century?

Knowledge to emancipate

Historians of popular education emphasize the vagueness of its definition

on a scientific level , while affirming its

importance for understanding our educational history. Is it just an approach aimed at giving the greatest number of people the opportunity to access knowledge? Popular education is much more than that.

At the same time an element of permanent education, lifelong training, with the ambition of an education accessible to all, it can be defined as a desire for individual and collective emancipation from active and concrete practices.

Providing everyone with access to knowledge and skills in order to emancipate themselves and transform society is an ideal that emerged from the French Revolution. But it is the beginning of the XIX

th century, with the rise of industrial society and capitalist, the ambition

of the people education and the emancipation of workers is emerging practice.

This

nascent popular education has many forms. The republican current, by creating, in 1866, the education

league , thinks of the supervision of young people outside school time, even before the development of secular and compulsory school.

The workers’ union movement offers around labor exchanges and

popular universities , a political training of workers. For their part, the Christian currents founded their own associations of popular education in the image of the Christian workers’ youth (JOC) and the Catholic agricultural youth (JAC).

A golden age?

The rise of popular education can be seen from the creation of paid vacations in 1936 and the progressive policy of the Popular Front implemented by the Minister of National Education Jean Zay and by the Secretary of State for youth and sports Léo Lagrange.

It was the beginning of popular education with the creation of Cemea (

training centers for active education methods ) in 1937 and multiple associations

of holiday camps , spaces for education and socialization of youth. The movement continued at the Liberation with the creation of the

National Federation of Francas (Mouvement des Francs et Franches Comarades) and the creation of

the Youth and Culture Houses (MJC) which perpetuate and amplify this popular education of access to culture and knowledge for all.

At the same time, popular education is

becoming institutionalized . In 1953, the national institute of youth and popular education (INJEP) federates the various movements and an official statute of professional animator is created. While perpetuating itself, popular education seems to lose sight of its emancipatory character from the social point of view by confining itself to the socio-cultural domain.

New areas of action?

In 1998, the creation of Attac illustrated this return to a political conception of popular education.

The social damage still exacerbated by the current health crisis requires, more than ever, an awareness of the growing inequalities in our society and

the worsening of poverty in France .

ATD Fourth World or Emmaüs, to name just these two emblematic associations, have actively participated for decades in the fight against social inequalities through popular education and training actions.

Should we therefore see in it, as a

report by the Economic and Social Council of May 2019 underlined , a “modern and pioneering concept” and a “permanent laboratory for innovation and active methods”? Because today we are witnessing a revival, a

bifurcation, specifies the sociologist Christian Maurel, or perhaps a return to the very sources of popular education.

Indeed, in May 2021, the note Injep the

factory public education specifies many possible areas of intervention of popular education in the twenty

th century: continuing education, popular universities, but also support measures urban policies, struggles against inequalities or all forms of discrimination.

Popular education is anchored in all areas and represents an educational lever for all social categories and all generations, like the work of the

Federation of Social Centers on Aging.

A social project in the 21st century

Because of its history, popular education has its pedagogical figures, like

Fernand Oury or

Gisèle de Failly . It also has its own pedagogies such as decision-making – “allowing individuals to decide what concerns them” –

social pedagogy , theorized in France in particular by

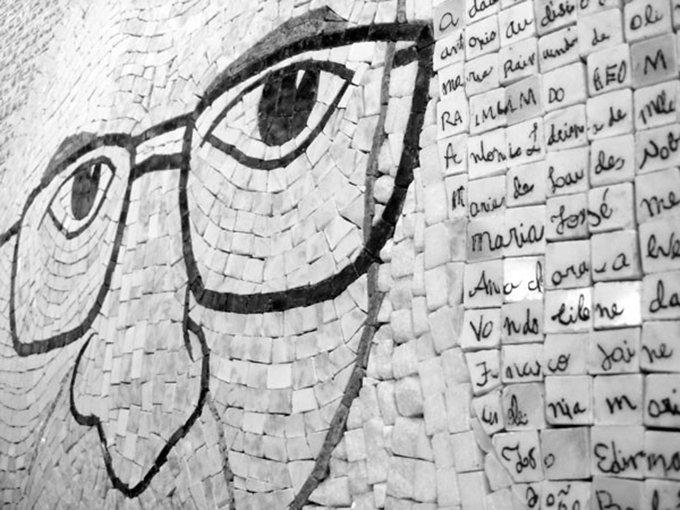

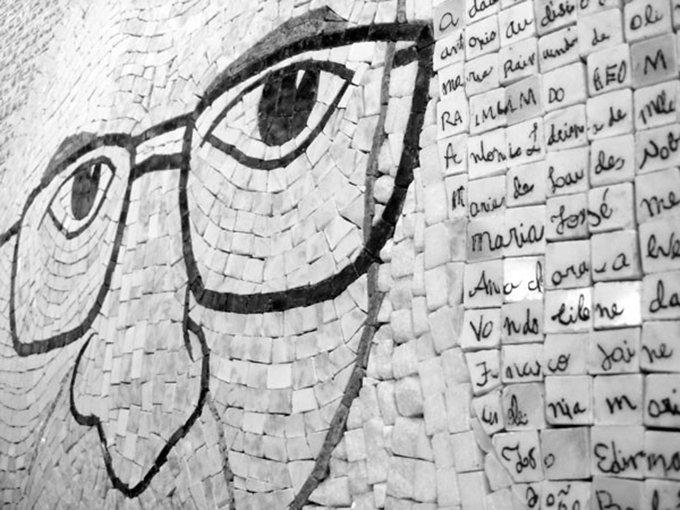

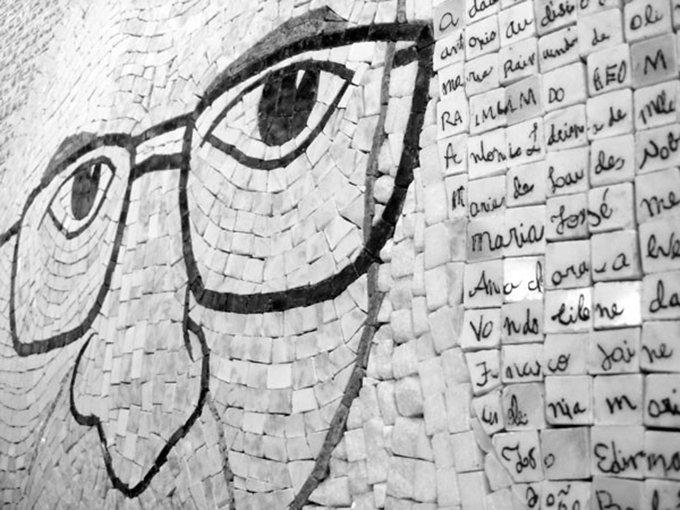

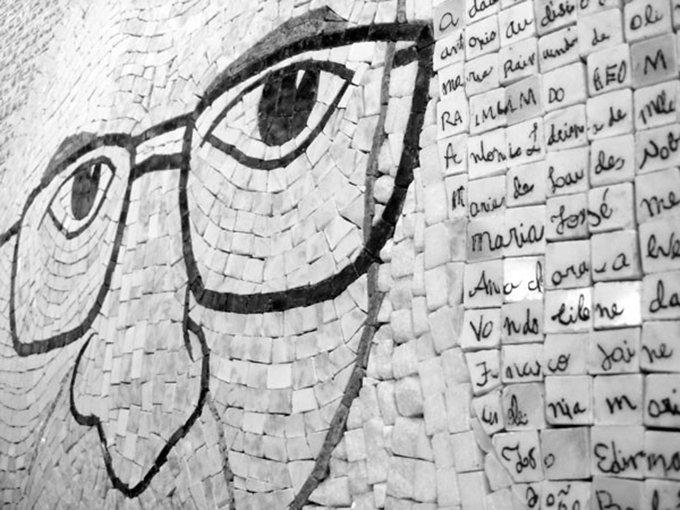

Laurent Ott , or critical pedagogies inspired by the Brazilian pedagogue

Paulo Freire .

The presence of

Philippe Meirieu , a great name in education, as the national presidency of Cemea is in this respect a symbol of this reaffirmation that

education can be at the heart of a social project.

But the vigor of popular education is also in this link between active methods and

education in politics underlining this need to rethink a living democracy where all inhabitants have a place, can act and influence decisions.

The fields of action of popular education in the twenty

th century are therefore countless. The desire to create

direct democratic activities , specific forms of public expression such as

gesticulated conferences or new educational spaces, such

as adventure fields that redefine the place of children in the city are just a few examples. of this educational and political dynamism.

Author Bios: Sylvain Wagnon is a University Professor in Educational Sciences, Faculty of Education, University of Montpellier and Mathieu Depoil is a Doctorate in Educational Science at Liderf – University of Montpellier, University Paul Valéry – Montpellier III

What do youth and cultural centers, youth hostels and scouting have in common? Each of these movements or associations is linked to what is called popular education, which intends to improve the functioning of society without the support of traditional institutions.

But how can this non-school educational process be defined more precisely? Popular education has a specific history, principles and practices. What does it represent today? How can it be a real political project and innovative education in XXI th century?

What do youth and cultural centers, youth hostels and scouting have in common? Each of these movements or associations is linked to what is called popular education, which intends to improve the functioning of society without the support of traditional institutions.

But how can this non-school educational process be defined more precisely? Popular education has a specific history, principles and practices. What does it represent today? How can it be a real political project and innovative education in XXI th century?

What do youth and cultural centers, youth hostels and scouting have in common? Each of these movements or associations is linked to what is called popular education, which intends to improve the functioning of society without the support of traditional institutions.

But how can this non-school educational process be defined more precisely? Popular education has a specific history, principles and practices. What does it represent today? How can it be a real political project and innovative education in XXI th century?

What do youth and cultural centers, youth hostels and scouting have in common? Each of these movements or associations is linked to what is called popular education, which intends to improve the functioning of society without the support of traditional institutions.

But how can this non-school educational process be defined more precisely? Popular education has a specific history, principles and practices. What does it represent today? How can it be a real political project and innovative education in XXI th century?