“The lights are off, shelves are in disarray and dust has coated every single book,” says Zabihullah Ehsas, my longtime friend and mentor, describing the current state of Khushal Baba Ketabtun, a library we established together in 2012. Our efforts represented an attempt to address the shortage of Pashto books in Mazar-i-Sharif, the cultural and economic hub of northern Afghanistan.

Funded by the Goethe-Institut, and holding a collection of nearly 4,000 volumes in Pashto, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan, the library quickly turned into a stomping ground for the city’s intellectuals, nurturing and hosting an array of literary programs — including literary critiques, poetry recitals and competitions, book reviews, guest speakers and anniversaries of renowned authors.

Now “it has been seven months that no one has peeked into the library,” Ehsas tells me via WhatsApp. I can hear a lump in his throat. “It is painful to see the distance between people and books grow.”

True.

The Taliban takeover last August hit Afghanistan’s reading culture and book industry especially hard. Libraries such as Khushal Baba Ketabtun, with its highly fertile and engaging environment, went quiet. The number of book stores is rapidly shrinking, and publishers and printing houses are in a deep economic crisis, with some already closed.

“The lights are off, shelves are in disarray and dust has coated every single book,” says Zabihullah Ehsas, my longtime friend and mentor, describing the current state of Khushal Baba Ketabtun, a library we established together in 2012. Our efforts represented an attempt to address the shortage of Pashto books in Mazar-i-Sharif, the cultural and economic hub of northern Afghanistan.

Funded by the Goethe-Institut, and holding a collection of nearly 4,000 volumes in Pashto, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan, the library quickly turned into a stomping ground for the city’s intellectuals, nurturing and hosting an array of literary programs — including literary critiques, poetry recitals and competitions, book reviews, guest speakers and anniversaries of renowned authors.

Now “it has been seven months that no one has peeked into the library,” Ehsas tells me via WhatsApp. I can hear a lump in his throat. “It is painful to see the distance between people and books grow.”

True.

The Taliban takeover last August hit Afghanistan’s reading culture and book industry especially hard. Libraries such as Khushal Baba Ketabtun, with its highly fertile and engaging environment, went quiet. The number of book stores is rapidly shrinking, and publishers and printing houses are in a deep economic crisis, with some already closed.

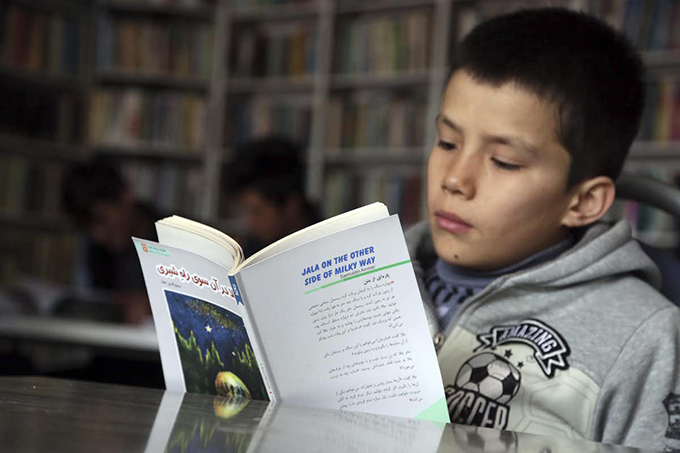

A boy reads at the Rahila library, in Kabul, in March 2019.

Squashed, neglected libraries

Suppressing regimes and widespread chaos over a span of 40 years squashed the public libraries and reading culture in Afghanistan. The communists cracked down on religious books and the mujahedeen burned communist books after toppling the last communist president, Mohammad Najibullah. In the mid-‘90s, the Taliban tried to further erase the cultural elements of the country. The destruction of Buddha statues in Bamyan was the boldest example of this rampage. When the United States-backed republic formed in 2001, a government engulfed by corruption and insurgency had little-to-no interest in rehabilitating the country’s libraries. They were largely neglected and remained non-functioning. As a faculty member at Balkh University in Mazar-i-Sharif, teaching Pashto linguistics and literature, I had observed the library on our campus for a decade before I fled the country in August. In a small, dimly lit, low-ceilinged hall, 32,000 books, at least according to official figures, were piled on wooden and metal shelves, creating narrow aisles. Nearly all of the books were outdated, the librarian told me. Untrained, he just kept a record of book borrowings. The library didn’t have a comprehensive database; anyone looking for a book had to search the shelves for it. The library had a handful of visitors, exclusively students and professors, who picked the books they needed for their research. No reading took place there! Unable to meet the needs of a book-hungry post-war nation, especially when the number of educated youths rapidly increased, these libraries gave room to privately run public libraries.Private initiatives promote reading culture

A panoply of initiatives were taken throughout the country to improve access to books and promote the culture of reading and literacy. One man in Kandahar, the heartland of the Taliban, opened a small library in a village that would turn into a national campaign for book donations. Eventually this became a movement, called PenPath Volunteers, that advocated for education in the most underserved communities. A woman in neighbouring Helmand founded a small library single-handedly, from her own personal savings, to provide a space for women to read. Another bright idea came from what became a Kabul-based non-profit organization, Charmaghz: young Afghans converted buses, rented from a state department, into mobile libraries. The initiative gave an adventurous ride and reading experience for the most underprivileged kids in Kabul. In eastern Afghanistan, a young Afghan turned his bicycle into a library, peddling books to Afghan villages. A well-known Afghan singer, Javed Amirkhil, joined him. Reading circles sprang up in Kabul, including a book club for kids, the Book Cottage and Kola Poshta, where topics such as hedonism, pleasure and sex were discussed. Numerous reading circles tried to reunite Afghans with a tradition they had lost to the perpetual conflict: reading.Publishers nurturing the readership

In 2001, when the international community intervened in Afghanistan and toppled the first Taliban regime, many of the exiled publishers and printing houses, especially those in Peshawar, returned. By 2013, the printing industry was already self-sufficient. As the republic was building and rehabilitating schools and universities, millions of textbooks were needed in a short period of time, providing an opportunity for dozens to invest in the book market; two of my friends and colleagues joined the race. In 2018, a New York Times story on this booming publishing market suggested the only things Afghanistan does not import are opium and books. Afghanistan has no operating national ISBN agency — the global registration authority for books — so it’s impossible to know how many books have been published in the country in recent decades. Publishers told me Afghanistan had become a member of the agency sometime around 2008, but by and large books continued to be published without ISBN numbers. Radio Azadi, Radio Free Europe’s Afghanistan Pashto-language broadcast, reported that hundreds of titles were published on an annual basis. But it came with a price. Not only did piracy become a real issue, but the books published, whether by private publishers or state institutions — universities or academies of sciences — largely fell short on substance. The authors, who usually self-sponsored their books’ publications, did not follow the rules of research. All that the editors at the publishing houses seemed to do was to proofread — sometimes badly.

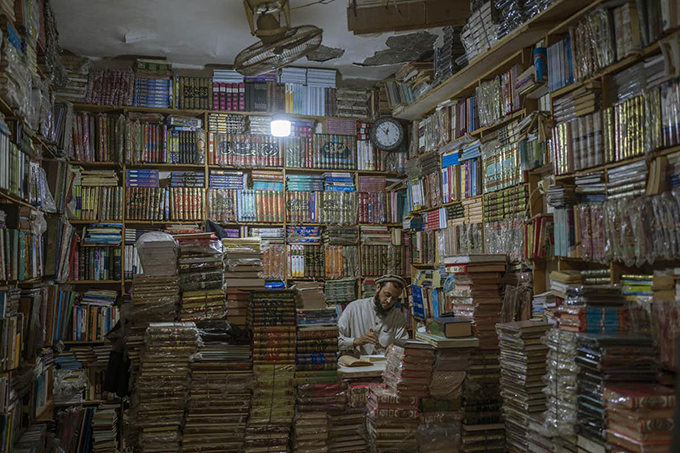

A bookshop owner repairs a book in Herat, Afghanistan, in November 2021. (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris)