Teacher supply and demand is a complex matter. The ultimate aim is to have a teacher in front of every class, now and for the foreseeable future. This also implies an ideal class size. The quality of teachers is obviously important too – and a topic for another occasion.

In South Africa, the ideal class size is tacit, and not explicit, as there are no class size norms. Instead, it is the available budget and negotiated teacher pay which drive the number of teachers, which in turn largely determines the average class size. But there are other factors at play too, as we’ll explain.

If South Africa were to lower the pupil-teacher ratio from the current 30 to a typical middle income country level of around 25, it would need an additional 100,000 teachers. Government spending on schooling is already fairly high, so it would be difficult to pay that many more teachers.

Is the problem that teachers in South Africa are paid too much? We conducted an international comparison, using household assets to stand in for purchasing power. We found that South African teachers’ purchasing power was not that different from that of teachers in other middle income countries.

There is a window of opportunity which has received insufficient attention. Soon there will be a large wave of retirements among South African teachers, peaking around 2030 and ending in 2040. New, younger – and lower paid – teachers will have to take their place. But this opportunity comes with questions around the capacity of universities to rapidly increase the output of teacher graduates.

Teacher supply and demand is a complex matter. The ultimate aim is to have a teacher in front of every class, now and for the foreseeable future. This also implies an ideal class size. The quality of teachers is obviously important too – and a topic for another occasion.

In South Africa, the ideal class size is tacit, and not explicit, as there are no class size norms. Instead, it is the available budget and negotiated teacher pay which drive the number of teachers, which in turn largely determines the average class size. But there are other factors at play too, as we’ll explain.

If South Africa were to lower the pupil-teacher ratio from the current 30 to a typical middle income country level of around 25, it would need an additional 100,000 teachers. Government spending on schooling is already fairly high, so it would be difficult to pay that many more teachers.

Is the problem that teachers in South Africa are paid too much? We conducted an international comparison, using household assets to stand in for purchasing power. We found that South African teachers’ purchasing power was not that different from that of teachers in other middle income countries.

There is a window of opportunity which has received insufficient attention. Soon there will be a large wave of retirements among South African teachers, peaking around 2030 and ending in 2040. New, younger – and lower paid – teachers will have to take their place. But this opportunity comes with questions around the capacity of universities to rapidly increase the output of teacher graduates.

Factors influencing class size

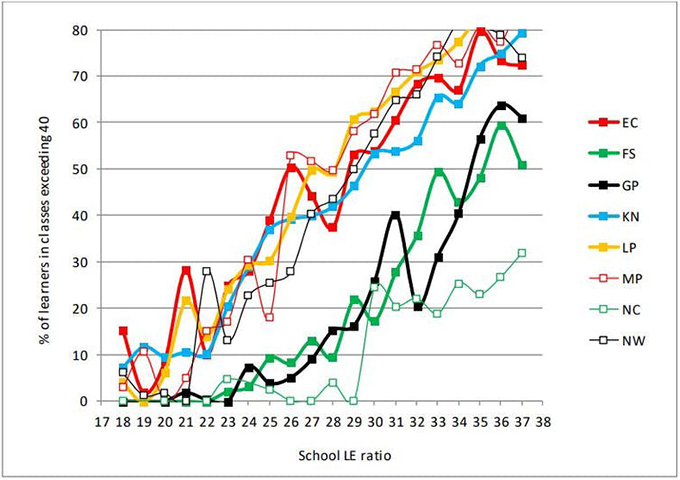

Around half of South Africa’s primary learners are in classes with more than 40 learners. About 15% are in classes exceeding 50 learners. The averages and inequality are considerably worse than what one sees in countries such as Chile, Indonesia, Morocco and Iran. What explains the inequality? There are four key factors. Firstly, though policy distributes teaching posts equitably, not all posts are filled all the time. Historically disadvantaged schools have the greatest difficulty filling posts. Secondly, the policy doesn’t take classrooms into account. Based on enrolment, 20 teaching posts could be allocated to a school with 15 classrooms. Thirdly, there’s evidence that poor timetabling and poor use of teaching time result in too many free periods for teachers, and too few classes being taught at any time. This is especially the case beyond Grade 3, where it becomes increasingly common for teachers to specialise in a curriculum subject. Fourthly, schools permitted to charge fees, which tend to be middle class schools, can employ additional teachers and thus reduce class sizes. The province a school is in plays a remarkably large role. Schools with similar learner-educator ratios end up with very different class sizes, depending on province. The following graph shows that in primary schools with an educator for every 32 learners, as an example, the percentage of the school’s learners in a class exceeding 40 learners differs vastly. In Free State and Gauteng, this figure is around 30% of learners. In other provinces, it more than double that.

Learner-educator ratio in South African provinces. Department of Basic Education.