The prominent model of information access before search engines became the norm – librarians and subject or search experts providing relevant information – was interactive, personalized, transparent and authoritative. Search engines are the primary way most people access information today, but entering a few keywords and getting a list of results ranked by some unknown function is not ideal.

A new generation of artificial intelligence-based information access systems, which includes Microsoft’s Bing/ChatGPT, Google/Bard and Meta/LLaMA, is upending the traditional search engine mode of search input and output. These systems are able to take full sentences and even paragraphs as input and generate personalized natural language responses.

At first glance, this might seem like the best of both worlds: personable and custom answers combined with the breadth and depth of knowledge on the internet. But as a researcher who studies the search and recommendation systems, I believe the picture is mixed at best.

AI systems like ChatGPT and Bard are built on large language models. A language model is a machine-learning technique that uses a large body of available texts, such as Wikipedia and PubMed articles, to learn patterns. In simple terms, these models figure out what word is likely to come next, given a set of words or a phrase. In doing so, they are able to generate sentences, paragraphs and even pages that correspond to a query from a user. On March 14, 2023, OpenAI announced the next generation of the technology, GPT-4, which works with both text and image input, and Microsoft announced that its conversational Bing is based on GPT-4.

The prominent model of information access before search engines became the norm – librarians and subject or search experts providing relevant information – was interactive, personalized, transparent and authoritative. Search engines are the primary way most people access information today, but entering a few keywords and getting a list of results ranked by some unknown function is not ideal.

A new generation of artificial intelligence-based information access systems, which includes Microsoft’s Bing/ChatGPT, Google/Bard and Meta/LLaMA, is upending the traditional search engine mode of search input and output. These systems are able to take full sentences and even paragraphs as input and generate personalized natural language responses.

At first glance, this might seem like the best of both worlds: personable and custom answers combined with the breadth and depth of knowledge on the internet. But as a researcher who studies the search and recommendation systems, I believe the picture is mixed at best.

AI systems like ChatGPT and Bard are built on large language models. A language model is a machine-learning technique that uses a large body of available texts, such as Wikipedia and PubMed articles, to learn patterns. In simple terms, these models figure out what word is likely to come next, given a set of words or a phrase. In doing so, they are able to generate sentences, paragraphs and even pages that correspond to a query from a user. On March 14, 2023, OpenAI announced the next generation of the technology, GPT-4, which works with both text and image input, and Microsoft announced that its conversational Bing is based on GPT-4.

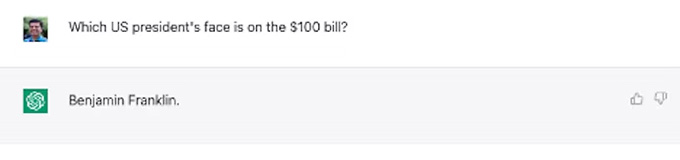

Opacity and ‘hallucinations’

However, there are plenty of downsides. First, consider what is at the heart of a large language model – a mechanism through which it connects the words and presumably their meanings. This produces an output that often seems like an intelligent response, but large language model systems are known to produce almost parroted statements without a real understanding. So, while the generated output from such systems might seem smart, it is merely a reflection of underlying patterns of words the AI has found in an appropriate context. This limitation makes large language model systems susceptible to making up or “hallucinating” answers. The systems are also not smart enough to understand the incorrect premise of a question and answer faulty questions anyway. For example, when asked which U.S. president’s face is on the $100 bill, ChatGPT answers Benjamin Franklin without realizing that Franklin was never president and that the premise that the $100 bill has a picture of a U.S. president is incorrect. The problem is that even when these systems are wrong only 10% of the time, you don’t know which 10%. People also don’t have the ability to quickly validate the systems’ responses. That’s because these systems lack transparency – they don’t reveal what data they are trained on, what sources they have used to come up with answers or how those responses are generated. For example, you could ask ChatGPT to write a technical report with citations. But often it makes up these citations – “hallucinating” the titles of scholarly papers as well as the authors. The systems also don’t validate the accuracy of their responses. This leaves the validation up to the user, and users may not have the motivation or skills to do so or even recognize the need to check an AI’s responses.

ChatGPT doesn’t know when a question doesn’t make sense, because it doesn’t know any facts. Screen capture by Chirag Shah