Email is the lifeblood of university communications: quick, easy, painless… and so very easy to get wrong.

We humans are a curious lot. We are highly social creatures but idiosyncratic. There is a lot of love, but also a lot of jostling for status and power. Academia, with its deeply middle class, coded language and manners is a real social challenge. Being an effective emailer in academia requires next level skills. It’s easy – all too easy – to get it wrong and, well – piss people off.

There are a couple of reasons you might want to write a ‘cold call’ email to an academic you don’t know:

- To seek help or feedback on your current project.

- To ask a favour: such as giving a presentation, supplying data or sending a paper that you can’t access.

- To ask for a job.

- To express admiration and seek to make a connection.

I asked academics on Twitter aand was surprised at the number of complaints about inappropriate and borderline unprofessional emails from colleagues and members of the public. Even if students are not the worst offenders, it’s good to know what sort of things are competing for attention in a typical academic inbox:

- Other academics complaining their work wasn’t cited in your latest paper (!)

- Emails about why your theory or findings are wrong (much easier than writing a paper rebutting the original work I suppose).

- Emails questioning your academic expertise. (This one seems to be a bit gendered, as @CJfrieman put it: “I am a woman writing about stone weapons. That makes a certain sort of guy mad”).

- Students asking you to do their work for them.

- People wanting information about your research participants (most projects will have specific ethics clearance that prevents sharing this kind of data).

- Legal threats. Yes. Apparently a lot of them from right-wing media types.

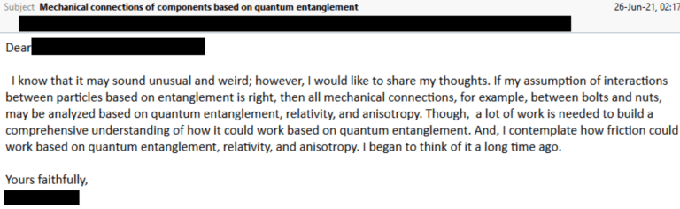

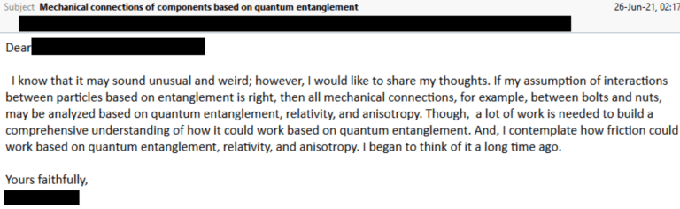

Finally, a special mention to members of the public who apparently send our physicist colleagues emails like this:

Or, um – this…

with thanks to @ad_mico for the examples and wow – I’m sorry!)

with thanks to @ad_mico for the examples and wow – I’m sorry!)

The cold call email is a fact of academic life, so being able to do it well is essential.

A week or so ago, my fellow bloggers Helen Kara and Pat Thomson approached me with an idea. Helen recently had an experience with someone harassing her with unreasonable requests. I’ve had my fair share of these too, so I could relate. They suggested we do some linked posts. Helen went first with her

10 tips for getting the best out of busy people, and here are my thoughts:

If you write to me, I will love hearing from you.

Honestly. I just like hearing I helped you – materially, emotionally, intellectually – it doesn’t matter. Academics in general love to hear their work has been a) read and b) enjoyed and used.

I’m lucky enough to get between 5 and 10 complimentary emails a week: the result of over a decade of blogging and well over half a million published words on the topic of doing a PhD. Some are a quick ‘thank you’ to say

the PhD is FINALLY finished! Others are heart felt outpourings, like this delightful example:

“…I’ve always found it natural and effortless to complain bitterly when the world, or the people in it, fail to conform completely to my complex set of needs and expectations. I have therefore made it a part of my new decade’s resolutions to also express my feelings when things go well.

My older, and even more repressed (in a gentlemanly, English way), brother did this when he recently told me he loved me. Actually he emailed the sentiment, as a face to face exchange of such profound intimacy could have provoked a cardiac infarction in one or both of us. I give him great credit for saying it, though, as such validation from an older, smarter and much more successful sibling meant a huge deal to me.

No don’t worry, I’m not going to tell you I love you, but I would like to express my thanks for the important, but comfortably understated, role you played in helping me navigate the Dark Night of the Soul that was my Phd journey; for providing a break from the reductionist, positivist world view represented by [discipline]… If I can summon the courage to express such sentiments verbally, I will do so next time I see you.”

Never hesitate to send a complimentary email, even if you have never met the person before. It makes the world just a little bit sweeter in difficult times.

Just tell me what you want from me.

People often complain academics are bad at responding to emails, which is true, but it’s hard to respond when someone doesn’t include a clear ‘ask’.

I believe if you don’t ask, you don’t get – so I always respond to an email with a genuine request. I’m happy to give out advice, directions to resources, and encouragement to anyone who writes to me. It’s my experience that most academics are the same, but most do not organise their email lives as well as I do. It’s easy for a genuine request email to fall to the end of the inbox and never get answered.

If you have a request to make of a busy person, state it as clearly (and politely) as you can. Don’t include ‘side threads’ – if you want something, make the email about that. If you have multiple requests of the same person, send multiple emails. I know this sounds like it would be more bothersome, but trust me: your email is more likely to get attention if it’s about one request. But…

Make it ok for me to say no

It helps me if you check first to see if I can do what you are asking.

For instance, I often get short notes from people who want me to copy edit or help them write their thesis. I say clearly on my

About Page that I don’t do this and I have resources and links to ethical service providers on my

Recommended page. I use a service called TextExpander that enables me to reply quickly to these requests with a couple of key strokes, but you might just never hear back from someone less organised than me.

A lot of people don’t like saying ‘no’, so they will avoid your email altogether.

The lesson here is that busy people are usually successful and helpful people too. Don’t be afraid to approach them, but do a bit of homework before approaching with your ask. I have more to say on the power of getting a person to say ‘no’ below, but while we’re on the topic of being approached…

Don’t tag me on Twitter unless you actually want to talk to me

Email is not the only way to talk to a busy person. Tagging is the practice of mentioning a user name in a social media post. This has the effect of ‘calling in’ the person tagged to join the conversation. It can be a quick way of getting attention and an answer to your questions.

I LOVE BEING TAGGED. Seriously. On Twitter, people often call me into a conversations they know will interest me. I’ve picked up so many useful papers, contacts and tools this way. The latest thing I discovered via this route was

connectedpapers.com (try it – I’ll wait here. You can thank me later). They also ask questions and these are useful to me too – a lot of my blog posts come out of questions people ask me on social media.

What I don’t love is being tagged in to boost the visibility of a product I don’t know about or want to endorse.

People who do this are gaming the algorithms; using my big follower count to ‘signal boost’ their offering. A lot of these people have frankly dodgy offerings and lately I have taken to just blocking anyone who does this immediately.

The point here is that manners are contextual: when the platform changes, you need to change your behaviour. If you want my attention to your new course or book, email me and ask, don’t just tag me in to boost your numbers – speaking of which…

If you want me to help you, invite me into your world

A small ask that draws on my expertise is absolutely ok – a pleasure even. Sharing something with me you think I will love is delightful. But consider this email, which I received recently:

“…Over the past few years, I have been running [online project] During that time, I have asked thousands of people of all ages to tell me about [a topic]. I’ve learned a lot. I’ve recently started sharing some of those insights on [my blog]. Another article I wrote on [topics] was published by [major website] and got more than 300,000 reads. There is clearly broad interest in the topic.

I am now in the process of writing a book tentatively titled [title]. My literary agent tells me that it’s time to start telling the world about it, which I am excited to do. I am a fan of your website and have noticed that many of the topics I have researched – which will become major sections in my book – relate to topics that your readers will be interested in…. I would like to invite you to consider writing about [my web project to collect email addresses to prove to the publisher that people will buy this book]…

…If you would prefer to wait until my book is published before writing about it, I would really appreciate your permission to mention that commitment in my book proposal that I am currently approaching publishers with.”

There’s a clear ask, but wow – it’s a big one. This person is essentially asking me to:

- Take an interest in their work when it’s not really related to my work.

- Read their articles.

- Review their online archive of material and blog posts.

- Connect their work to my work and write a post that pulls you into their mailing list, or commit to backing a book I have never read, which will…

- Help them get a book deal

I’m going to be kind and think this person is just excited by their ideas and wants me to be excited too, but in this case it misfired and made me annoyed. I was annoyed because this person is asking for a significant portion of my time. Time is a precious resource.

If I was to do everything this whole list, it would take me days. I could do this, or I could spend my time teaching, marking up a student manuscript, responding to genuine problems and queries from distressed students around the world, making algorithms and improving

PostAc to help PhD students find jobs outside academia, writing committee papers and, well – you get the picture.

Influencing me is easier than you think…

I’ve helped many people get book deals and jobs by drawing attention to their talents, either online or via my network of contacts. Helping people succeed is something I love to do, but don’t ask me to go on this whole journey in one email. Work on influencing me instead, and you can do this by making it ok for me to say ‘no’.

Remember I said earlier that getting someone to say ‘no’ is powerful? It’s much more powerful than you think.

In his amazing book ‘

Influence: the psychology of persuasion‘ Robert Cialdini outlines the tactics used by real estate agents and car sales people to make people spend more than they really want to. One of the most effective techniques is the small ask which the person can easily refused, followed by a bigger ask which they find harder to resist. (I highly recommend you read this book as it’s a bit scary how easy it is to manipulate humans).

How might this tactic have worked for the person writing to me about their book deal?

He should have started by writing to me with a link to his short article, telling me why I might be interested and inviting me to read it. Then he should have waited to see how I reacted. If I wrote back saying “Hey nice article”, he had my attention. Then he could have moved to the next ask – the one designed to get me to say ‘no’. This is the time to point out that he had a similar blog to me and are working on a book deal. As a published author, would I be interested in reading the proposal and giving some feedback?

Importantly, he should phrase request in a way that makes it crystal clear it would be ok to say ‘no’. Something like “I know you are very busy and this is a big ask. I just value your interest and hope I can let you know if I am successful?”

I will probably say no to reading the proposal but – and here’s the critical part – I would also be a bit relieved that he made it easy for me to say so with grace. What I might not realise (unless I have read Cialdini’s book) is that saying ‘no’ has primed me to want to be more helpful in the future.

Getting me to say ‘no’ works because it troubles my

identity as a helpful person. If you make me feel like I am being unhelpful, I will feel compelled to help you more. I am deeply compelled to shore up my self image to myself and others. Put simply, by making it easy for me to say ‘no’ you actually prepare me to say yes. The next ask might be small – would I review the book for the publisher? Well, ok – I found that blog post interesting after all and I had previously been unhelpful. I could make it up to him this way.

Fast forward a year or so and I will be blurbing your published book and we will have a lovely friendship.

Instead, this person got a cool ‘thanks for letting me know about your project but I don’t have time to assist’ email.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end of this blog post. I hope that some of these insights help you get what you need from busy people and I hope I get an email from you one day!

Email is the lifeblood of university communications: quick, easy, painless… and so very easy to get wrong.

We humans are a curious lot. We are highly social creatures but idiosyncratic. There is a lot of love, but also a lot of jostling for status and power. Academia, with its deeply middle class, coded language and manners is a real social challenge. Being an effective emailer in academia requires next level skills. It’s easy – all too easy – to get it wrong and, well – piss people off.

There are a couple of reasons you might want to write a ‘cold call’ email to an academic you don’t know:

Email is the lifeblood of university communications: quick, easy, painless… and so very easy to get wrong.

We humans are a curious lot. We are highly social creatures but idiosyncratic. There is a lot of love, but also a lot of jostling for status and power. Academia, with its deeply middle class, coded language and manners is a real social challenge. Being an effective emailer in academia requires next level skills. It’s easy – all too easy – to get it wrong and, well – piss people off.

There are a couple of reasons you might want to write a ‘cold call’ email to an academic you don’t know:

Or, um – this…

Or, um – this…

with thanks to @ad_mico for the examples and wow – I’m sorry!)

The cold call email is a fact of academic life, so being able to do it well is essential.

A week or so ago, my fellow bloggers Helen Kara and Pat Thomson approached me with an idea. Helen recently had an experience with someone harassing her with unreasonable requests. I’ve had my fair share of these too, so I could relate. They suggested we do some linked posts. Helen went first with her 10 tips for getting the best out of busy people, and here are my thoughts:

If you write to me, I will love hearing from you.

Honestly. I just like hearing I helped you – materially, emotionally, intellectually – it doesn’t matter. Academics in general love to hear their work has been a) read and b) enjoyed and used.

I’m lucky enough to get between 5 and 10 complimentary emails a week: the result of over a decade of blogging and well over half a million published words on the topic of doing a PhD. Some are a quick ‘thank you’ to say the PhD is FINALLY finished! Others are heart felt outpourings, like this delightful example:

“…I’ve always found it natural and effortless to complain bitterly when the world, or the people in it, fail to conform completely to my complex set of needs and expectations. I have therefore made it a part of my new decade’s resolutions to also express my feelings when things go well.

My older, and even more repressed (in a gentlemanly, English way), brother did this when he recently told me he loved me. Actually he emailed the sentiment, as a face to face exchange of such profound intimacy could have provoked a cardiac infarction in one or both of us. I give him great credit for saying it, though, as such validation from an older, smarter and much more successful sibling meant a huge deal to me.

No don’t worry, I’m not going to tell you I love you, but I would like to express my thanks for the important, but comfortably understated, role you played in helping me navigate the Dark Night of the Soul that was my Phd journey; for providing a break from the reductionist, positivist world view represented by [discipline]… If I can summon the courage to express such sentiments verbally, I will do so next time I see you.”

Never hesitate to send a complimentary email, even if you have never met the person before. It makes the world just a little bit sweeter in difficult times.

Just tell me what you want from me.

People often complain academics are bad at responding to emails, which is true, but it’s hard to respond when someone doesn’t include a clear ‘ask’.

I believe if you don’t ask, you don’t get – so I always respond to an email with a genuine request. I’m happy to give out advice, directions to resources, and encouragement to anyone who writes to me. It’s my experience that most academics are the same, but most do not organise their email lives as well as I do. It’s easy for a genuine request email to fall to the end of the inbox and never get answered.

If you have a request to make of a busy person, state it as clearly (and politely) as you can. Don’t include ‘side threads’ – if you want something, make the email about that. If you have multiple requests of the same person, send multiple emails. I know this sounds like it would be more bothersome, but trust me: your email is more likely to get attention if it’s about one request. But…

Make it ok for me to say no

It helps me if you check first to see if I can do what you are asking.

For instance, I often get short notes from people who want me to copy edit or help them write their thesis. I say clearly on my About Page that I don’t do this and I have resources and links to ethical service providers on my Recommended page. I use a service called TextExpander that enables me to reply quickly to these requests with a couple of key strokes, but you might just never hear back from someone less organised than me.

A lot of people don’t like saying ‘no’, so they will avoid your email altogether.

The lesson here is that busy people are usually successful and helpful people too. Don’t be afraid to approach them, but do a bit of homework before approaching with your ask. I have more to say on the power of getting a person to say ‘no’ below, but while we’re on the topic of being approached…

Don’t tag me on Twitter unless you actually want to talk to me

Email is not the only way to talk to a busy person. Tagging is the practice of mentioning a user name in a social media post. This has the effect of ‘calling in’ the person tagged to join the conversation. It can be a quick way of getting attention and an answer to your questions.

I LOVE BEING TAGGED. Seriously. On Twitter, people often call me into a conversations they know will interest me. I’ve picked up so many useful papers, contacts and tools this way. The latest thing I discovered via this route was connectedpapers.com (try it – I’ll wait here. You can thank me later). They also ask questions and these are useful to me too – a lot of my blog posts come out of questions people ask me on social media.

What I don’t love is being tagged in to boost the visibility of a product I don’t know about or want to endorse.

People who do this are gaming the algorithms; using my big follower count to ‘signal boost’ their offering. A lot of these people have frankly dodgy offerings and lately I have taken to just blocking anyone who does this immediately.

The point here is that manners are contextual: when the platform changes, you need to change your behaviour. If you want my attention to your new course or book, email me and ask, don’t just tag me in to boost your numbers – speaking of which…

If you want me to help you, invite me into your world

A small ask that draws on my expertise is absolutely ok – a pleasure even. Sharing something with me you think I will love is delightful. But consider this email, which I received recently:

“…Over the past few years, I have been running [online project] During that time, I have asked thousands of people of all ages to tell me about [a topic]. I’ve learned a lot. I’ve recently started sharing some of those insights on [my blog]. Another article I wrote on [topics] was published by [major website] and got more than 300,000 reads. There is clearly broad interest in the topic.

I am now in the process of writing a book tentatively titled [title]. My literary agent tells me that it’s time to start telling the world about it, which I am excited to do. I am a fan of your website and have noticed that many of the topics I have researched – which will become major sections in my book – relate to topics that your readers will be interested in…. I would like to invite you to consider writing about [my web project to collect email addresses to prove to the publisher that people will buy this book]…

…If you would prefer to wait until my book is published before writing about it, I would really appreciate your permission to mention that commitment in my book proposal that I am currently approaching publishers with.”

There’s a clear ask, but wow – it’s a big one. This person is essentially asking me to:

with thanks to @ad_mico for the examples and wow – I’m sorry!)

The cold call email is a fact of academic life, so being able to do it well is essential.

A week or so ago, my fellow bloggers Helen Kara and Pat Thomson approached me with an idea. Helen recently had an experience with someone harassing her with unreasonable requests. I’ve had my fair share of these too, so I could relate. They suggested we do some linked posts. Helen went first with her 10 tips for getting the best out of busy people, and here are my thoughts:

If you write to me, I will love hearing from you.

Honestly. I just like hearing I helped you – materially, emotionally, intellectually – it doesn’t matter. Academics in general love to hear their work has been a) read and b) enjoyed and used.

I’m lucky enough to get between 5 and 10 complimentary emails a week: the result of over a decade of blogging and well over half a million published words on the topic of doing a PhD. Some are a quick ‘thank you’ to say the PhD is FINALLY finished! Others are heart felt outpourings, like this delightful example:

“…I’ve always found it natural and effortless to complain bitterly when the world, or the people in it, fail to conform completely to my complex set of needs and expectations. I have therefore made it a part of my new decade’s resolutions to also express my feelings when things go well.

My older, and even more repressed (in a gentlemanly, English way), brother did this when he recently told me he loved me. Actually he emailed the sentiment, as a face to face exchange of such profound intimacy could have provoked a cardiac infarction in one or both of us. I give him great credit for saying it, though, as such validation from an older, smarter and much more successful sibling meant a huge deal to me.

No don’t worry, I’m not going to tell you I love you, but I would like to express my thanks for the important, but comfortably understated, role you played in helping me navigate the Dark Night of the Soul that was my Phd journey; for providing a break from the reductionist, positivist world view represented by [discipline]… If I can summon the courage to express such sentiments verbally, I will do so next time I see you.”

Never hesitate to send a complimentary email, even if you have never met the person before. It makes the world just a little bit sweeter in difficult times.

Just tell me what you want from me.

People often complain academics are bad at responding to emails, which is true, but it’s hard to respond when someone doesn’t include a clear ‘ask’.

I believe if you don’t ask, you don’t get – so I always respond to an email with a genuine request. I’m happy to give out advice, directions to resources, and encouragement to anyone who writes to me. It’s my experience that most academics are the same, but most do not organise their email lives as well as I do. It’s easy for a genuine request email to fall to the end of the inbox and never get answered.

If you have a request to make of a busy person, state it as clearly (and politely) as you can. Don’t include ‘side threads’ – if you want something, make the email about that. If you have multiple requests of the same person, send multiple emails. I know this sounds like it would be more bothersome, but trust me: your email is more likely to get attention if it’s about one request. But…

Make it ok for me to say no

It helps me if you check first to see if I can do what you are asking.

For instance, I often get short notes from people who want me to copy edit or help them write their thesis. I say clearly on my About Page that I don’t do this and I have resources and links to ethical service providers on my Recommended page. I use a service called TextExpander that enables me to reply quickly to these requests with a couple of key strokes, but you might just never hear back from someone less organised than me.

A lot of people don’t like saying ‘no’, so they will avoid your email altogether.

The lesson here is that busy people are usually successful and helpful people too. Don’t be afraid to approach them, but do a bit of homework before approaching with your ask. I have more to say on the power of getting a person to say ‘no’ below, but while we’re on the topic of being approached…

Don’t tag me on Twitter unless you actually want to talk to me

Email is not the only way to talk to a busy person. Tagging is the practice of mentioning a user name in a social media post. This has the effect of ‘calling in’ the person tagged to join the conversation. It can be a quick way of getting attention and an answer to your questions.

I LOVE BEING TAGGED. Seriously. On Twitter, people often call me into a conversations they know will interest me. I’ve picked up so many useful papers, contacts and tools this way. The latest thing I discovered via this route was connectedpapers.com (try it – I’ll wait here. You can thank me later). They also ask questions and these are useful to me too – a lot of my blog posts come out of questions people ask me on social media.

What I don’t love is being tagged in to boost the visibility of a product I don’t know about or want to endorse.

People who do this are gaming the algorithms; using my big follower count to ‘signal boost’ their offering. A lot of these people have frankly dodgy offerings and lately I have taken to just blocking anyone who does this immediately.

The point here is that manners are contextual: when the platform changes, you need to change your behaviour. If you want my attention to your new course or book, email me and ask, don’t just tag me in to boost your numbers – speaking of which…

If you want me to help you, invite me into your world

A small ask that draws on my expertise is absolutely ok – a pleasure even. Sharing something with me you think I will love is delightful. But consider this email, which I received recently:

“…Over the past few years, I have been running [online project] During that time, I have asked thousands of people of all ages to tell me about [a topic]. I’ve learned a lot. I’ve recently started sharing some of those insights on [my blog]. Another article I wrote on [topics] was published by [major website] and got more than 300,000 reads. There is clearly broad interest in the topic.

I am now in the process of writing a book tentatively titled [title]. My literary agent tells me that it’s time to start telling the world about it, which I am excited to do. I am a fan of your website and have noticed that many of the topics I have researched – which will become major sections in my book – relate to topics that your readers will be interested in…. I would like to invite you to consider writing about [my web project to collect email addresses to prove to the publisher that people will buy this book]…

…If you would prefer to wait until my book is published before writing about it, I would really appreciate your permission to mention that commitment in my book proposal that I am currently approaching publishers with.”

There’s a clear ask, but wow – it’s a big one. This person is essentially asking me to: