In the past few decades, several phenomena have led to excited speculation in the scientific community that they might indeed be indications that there is extraterrestrial life. It will no doubt happen again.

Recently, two very different examples sparked excitement. In 2017, it was the mystery interstellar object ‘Oumuamua. And in 2021, it was the possible discovery of the gas phosphine in the clouds of Venus.

In both cases, it seemed possible that the phenomenon indicated some kind of extraterrestrial biological source. Notably, physicist Avi Loeb from Harvard University argued in favour of the oddly shaped ‘Oumuamua being an alien spaceship.

And phosphine in the atmosphere of a rocky planet is proposed to be a strong signature for life, as it is continuously produced by microbes on Earth.

These are just two of the latest cases of a long list of examples of such initially promising phenomena. But although a few of the examples are still controversial, most have turned out to have other explanations (it wasn’t aliens).

So how can we be sure we’ve come to the right conclusion for something as subtle as the presence of a certain gas or a strange looking space rock? In our new paper published in the journal Astrobiology, we have proposed a technique for reliably evaluating such evidence.

The word “possible” is strange, with a rather unfortunate degree of flexibility. There’s a sense in which it is possible that I’ll meet King Charles III today, but at the same time it is extraordinarily unlikely.

Many shouts of: “It might be aliens!” should be interpreted in this (strained) sense. By contrast, we often use the word “might” to express something that has high probability, as in “it might snow today.”

The concept of possibility incorporates these extremes, and everything in-between. Newspapers might capitalise on this flexibility with a cheeky headline that appears to indicate that something is a bit more exciting than it actually is. But the scientific world needs to express itself with rigour, transparently conveying the degree of confidence justified by the evidence.

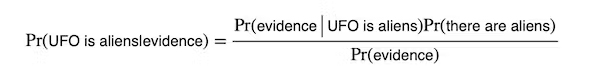

Some would turn to Bayes’ Theorem, a common statistical formula, which gives the probability (Pr) of something, given some evidence.

One could, optimistically, input the available evidence into the Bayes formula, and achieve as output a number between 0 and 1 (where 0.5 is a 50:50 chance that a signal is produced by aliens). But the Bayesian approach doesn’t really help when it comes to extraterrestrial life.

In the past few decades, several phenomena have led to excited speculation in the scientific community that they might indeed be indications that there is extraterrestrial life. It will no doubt happen again.

Recently, two very different examples sparked excitement. In 2017, it was the mystery interstellar object ‘Oumuamua. And in 2021, it was the possible discovery of the gas phosphine in the clouds of Venus.

In both cases, it seemed possible that the phenomenon indicated some kind of extraterrestrial biological source. Notably, physicist Avi Loeb from Harvard University argued in favour of the oddly shaped ‘Oumuamua being an alien spaceship.

And phosphine in the atmosphere of a rocky planet is proposed to be a strong signature for life, as it is continuously produced by microbes on Earth.

These are just two of the latest cases of a long list of examples of such initially promising phenomena. But although a few of the examples are still controversial, most have turned out to have other explanations (it wasn’t aliens).

So how can we be sure we’ve come to the right conclusion for something as subtle as the presence of a certain gas or a strange looking space rock? In our new paper published in the journal Astrobiology, we have proposed a technique for reliably evaluating such evidence.

The word “possible” is strange, with a rather unfortunate degree of flexibility. There’s a sense in which it is possible that I’ll meet King Charles III today, but at the same time it is extraordinarily unlikely.

Many shouts of: “It might be aliens!” should be interpreted in this (strained) sense. By contrast, we often use the word “might” to express something that has high probability, as in “it might snow today.”

The concept of possibility incorporates these extremes, and everything in-between. Newspapers might capitalise on this flexibility with a cheeky headline that appears to indicate that something is a bit more exciting than it actually is. But the scientific world needs to express itself with rigour, transparently conveying the degree of confidence justified by the evidence.

Some would turn to Bayes’ Theorem, a common statistical formula, which gives the probability (Pr) of something, given some evidence.

One could, optimistically, input the available evidence into the Bayes formula, and achieve as output a number between 0 and 1 (where 0.5 is a 50:50 chance that a signal is produced by aliens). But the Bayesian approach doesn’t really help when it comes to extraterrestrial life.

The Bayesian formula for alien evidence, produced by Anders Sandberg, University of Oxford. Author provided

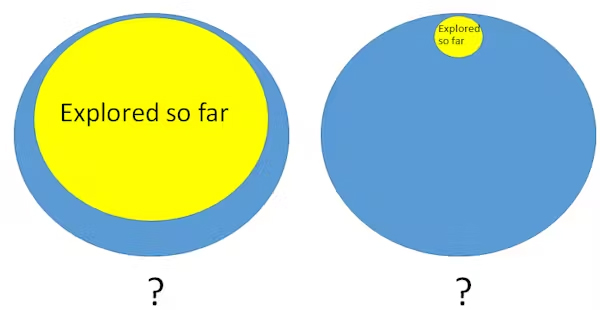

How much of the relevant possibility space have we explored? Peter Vickers, CC BY-SA

New approaches

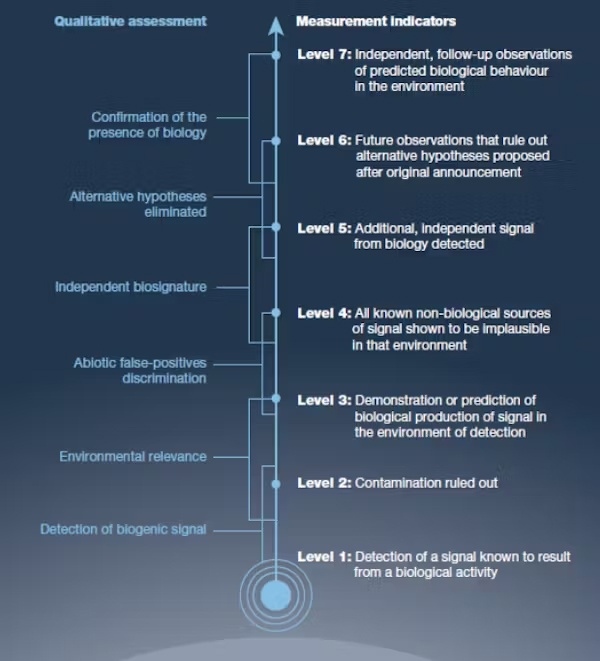

In 2021, a Nasa-affiliated group published a paper setting out the Confidence of Life Detection (CoLD) framework, designed to solve this problem. It recommends seven steps to verifying a discovery, from ruling out contamination to getting follow-up observations of a predicted biological signal in the same region.

The ‘CoLD’ framework. (Green et al., 2021), with permission, Author provided (no reuse)

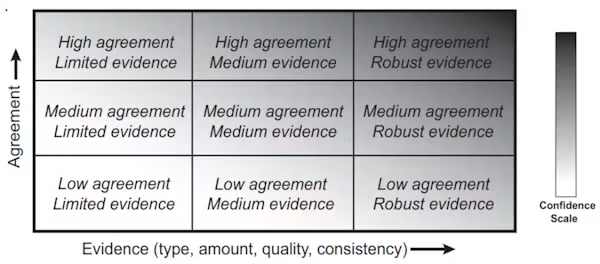

The IPCC uncertainty framework. Mastrandrea et al. (2010), with permission., Author provided (no reuse)