Imagine you’re a young samurai in Japan in 1701. You have to make a difficult choice between an impoverished life in exile, or the prospect of almost certain death while trying to avenge the death of your dishonored lord. Which do you choose?

“Ako: A Tale of Loyalty,” a video game built in 2020, takes players along a difficult journey through early modern Japan filled with decisions like this one. It’s become an essential component of my classes on Japanese history, but it wasn’t developed by a professional game studio. Instead, it was created by a team of four undergraduate history majors with no specialized training.

Imagine you’re a young samurai in Japan in 1701. You have to make a difficult choice between an impoverished life in exile, or the prospect of almost certain death while trying to avenge the death of your dishonored lord. Which do you choose?

“Ako: A Tale of Loyalty,” a video game built in 2020, takes players along a difficult journey through early modern Japan filled with decisions like this one. It’s become an essential component of my classes on Japanese history, but it wasn’t developed by a professional game studio. Instead, it was created by a team of four undergraduate history majors with no specialized training.

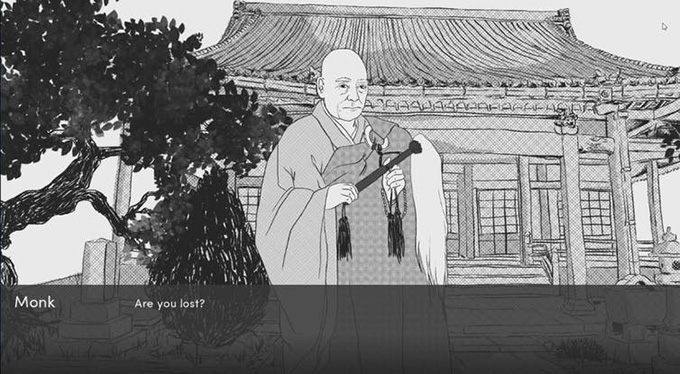

Loading screen for the ‘Ako’ visual novel game. Epoch: History Games Initiative/University of Texas at Austin

The gaming revolution

Nearly two-thirds of American adults play video games, and that figure rises steadily each year. Fueled by stay-at-home orders and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, global gaming sales rose to nearly US$180 billion in 2020. Among university students, video games are utterly pervasive. When I ask my classes who consumes video game content, either as a player or via streaming services like Twitch, it’s rare that a single student’s hand is not raised. Schools and colleges have rushed to respond to these trends. Programs like Gamestar Mechanic or Scratch help K-12 students learn basic coding skills, while many universities, including my own, have introduced game design majors to train the next generation of developers. History professors, however, have been slower to embrace video games as teaching tools. Part of the problem is that the historical content contained within games is often, with some exceptions, repetitive and superficial.

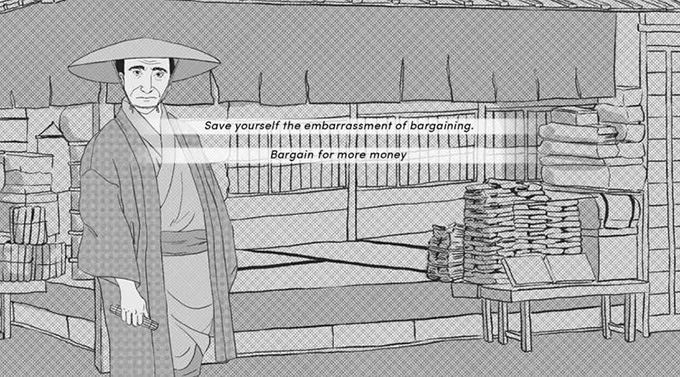

Example of a player decision. Epoch: History Games Initiative/University of Texas at Austin,

Designing humanities games

In 2020, I asked four undergraduate history majors to design a fully functional video game with a clear educational payoff built around a controversial episode in Japanese history. I was motivated by two ideas. First, I wanted to move beyond a standard reliance on academic essays. While I still assign essays, many students find them fairly passive exercises which don’t stimulate deep engagement with a topic. Second, I was convinced that university professors need to get into the business of producing games content. To be clear, we’re not going to design anything even close to what comes out of professional studios. But we can produce compelling games that are ready to be used both in colleges and – equally important – K-12 classrooms, where teachers are always looking for vetted scholarly content. A conventional academic essay is intended for just one person, the professor. But a video game produced by a group of committed undergraduates can be played by thousands of students at different institutions.

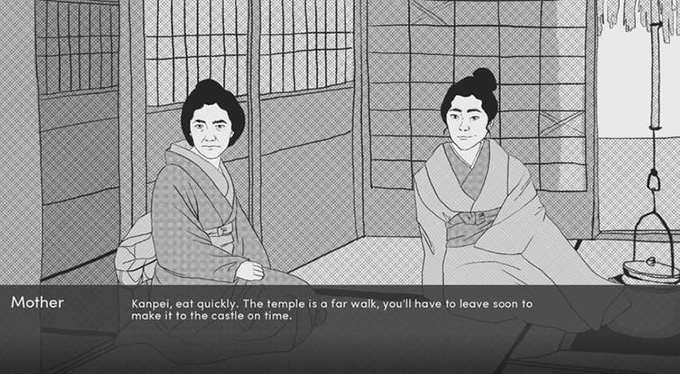

The main character’s mother and sister. Epoch: History Games Initiative/University of Texas at Austin

Learning by design

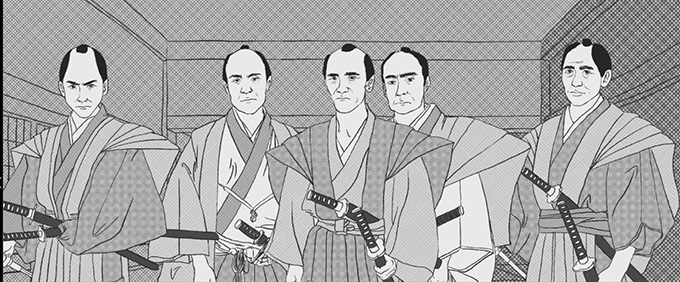

The team’s first task was to design a believable central character. Successful games push players to emotionally invest in their characters and the choices they make. In the case of “Ako,” the design team created a young samurai named Kanpei Hashimoto who was grounded in the period but also easy to relate to as a young person struggling to find his way in a complex world. From there, the team created branching storylines punctuated by clear decisions. In total, “Ako” has five possible outcomes depending on the choices a player makes. Numerous smaller decisions along the way open up additional ways to navigate the game. The next step was dialogue. A typical academic essay is around 2,500 words, and students often complain about how difficult it is to fill the required pages. In contrast, the “Ako” team wrote over 30,000 words of dialogue. It required extensive research. What would a samurai family have eaten for breakfast? How much did it cost to buy a “kaimyō,” or posthumous Buddhist name, for a deceased parent? How long did it take to make the oiled paper umbrellas, called “wagasa,” that many poor samurai sold to survive?

Engaging with different characters in the game. Epoch: History Games Initiative/University of Texas at Austin