In early April 2025, the Trump administration

terminated the immigration statuses of thousands of international students listed in a government database, meaning they no longer had legal permission to be in the country. Some students self-deported instead of facing deportation.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security recently announced that it would

reverse the terminations after courts across the country determined they did not have merit.

These moves come as the White House seeks to enhance

vetting and screening of all foreign nationals.

The State Department in March announced plans to use artificial intelligence to

review international students’ social media accounts.

As an administrator and scholar who specializes in

international higher education, I know that international students in the United States have long been subjected to a high level of

vetting, screening and monitoring.

Inserting additional bureaucracy into current processes could make the U.S. a less attractive study destination. I believe this would ultimately hamper the Trump administration’s ability to achieve its “

America First” priorities related to the economy, science and technology, and national security.

International students in the US

The U.S. has long been the

global leader in attracting international students. But

competition for these students is increasing as other countries, such as Germany and South Korea, enact

strategies for attracting international education.

The U.S. hosts 16% of all students studying outside of their home country, down from 22% in 2014 and 28% in 2001, according to the

Institute of International Education. Of the more than 1 million international students who were present in the U.S. during the 2023-2024 academic year, 54% came from just two countries,

China and India.

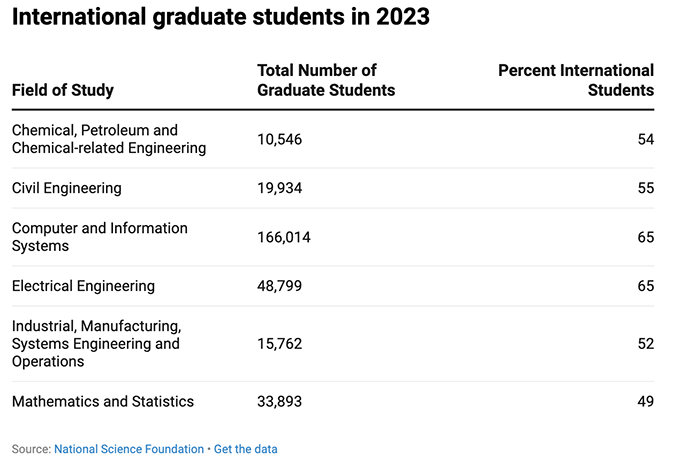

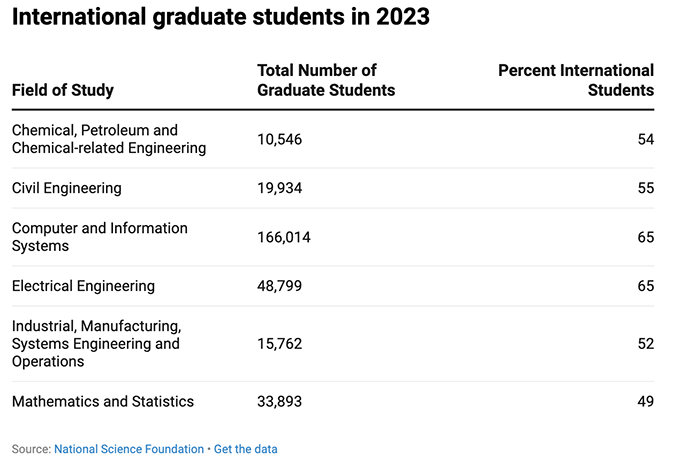

Most

international students pursue graduate degrees in

STEM fields – science, technology, engineering and mathematics. And, according to the

National Science Foundation, international students make up a significant portion of enrollment at the master’s and doctoral levels.

How international students are screened

International students in the U.S. are already subjected to intense screening and continuous monitoring. These measures include:

• Vetting the student’s school. Before they can apply for a visa, international students must be admitted to a school

authorized by the Department of Homeland Security to enroll people on student visas.

• Vetting at the embassy. As part of the

visa application process, international students are subjected to

national security reviews carried out by various intelligence and law enforcement agencies. In some cases, such as when a U.S. consular officer in their home country decides that more information is required from external sources to determine visa eligibility, additional screenings occur. That is done through a process known as

administrative processing.

• Vetting upon arrival. When they arrive in the U.S., international students are again screened by a

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer. If the officer is unable to verify any information, the student is sent to

secondary inspection, a secure interview area where the student waits while officers complete additional assessment. The student is then either admitted to the U.S. or forced to depart the country.

• Ongoing monitoring while in the U.S. If permitted to enter the country, students must enroll full time, earn good grades and notify their school within 10 days of substantive changes to their circumstances.

Examples include a change to their address, academic major or financial sponsor. And school officials are required to

report this information to the Student and Exchange Visitor Program, part of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s National Security Investigations Division.

Students participating in temporary, postgraduation training programs must continue to

comply with reporting requirements. And certain STEM graduates, and their employers, are subject to

additional requirements. They include

certification of training plans, annual evaluations and site visits.

Most

international students prefer to study in the U.S., recent research shows. But they are willing to change their preferences as other countries introduce friendlier visa policies, such as more flexible

post-study work opportunities and

lower visa costs.

Given the current level of screening and monitoring already imposed on international students in the U.S., it is unclear how additional measures would add value.

Critical to an America First agenda

President Donald Trump’s “America First” agenda

aims to grow the U.S. economy.

It also intends to maintain U.S.

leadership in science and technology and

enhance national security.

Trump administration officials have underlined the importance of recruiting top global talent.

And Trump has said that international students who graduate from U.S. colleges should be awarded a green card with their degree.

During the 2023-2024 academic year, international students contributed

US$43.8 billion to the U.S. economy through tuition and living expenses, which supported an estimated 378,175 U.S. jobs.

Their

contributions don’t end following graduation, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Many go on to launch successful startups at a rate that is eight to nine times higher than their domestic peers. In fact,

25% of billion-dollar companies in the U.S. were founded by a former international student.

Such companies include Eventbrite, Grammarly, Moderna, OpenAI, Robinhood and SpaceX.

International students also help the

U.S. maintain global leadership in STEM.

Consider that

45% of STEM workers in the U.S. holding a doctoral degree were born outside the U.S.

A 2024 report cautions that the

U.S. is failing to develop domestic STEM talent at all levels of the education system. Just 3.2% of U.S. high school graduates are estimated to enter the STEM workforce.

Moreover, the country’s ability to attract and retain

international STEM talent is decreasing due to immigration restrictions and increased global competition.

Finally, international students are critical to establishing global networks and promoting

soft power diplomacy. This is evidenced by the U.S. having

graduated more world leaders than any other nation.

Further restricting the ability of international students to study in the U.S. will ultimately

redirect talent to other countries, allies and adversaries alike.

Author Bio: David L. Di Maria is Vice Provost for Global Engagement at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County

In early April 2025, the Trump administration terminated the immigration statuses of thousands of international students listed in a government database, meaning they no longer had legal permission to be in the country. Some students self-deported instead of facing deportation.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security recently announced that it would reverse the terminations after courts across the country determined they did not have merit.

These moves come as the White House seeks to enhance vetting and screening of all foreign nationals.

The State Department in March announced plans to use artificial intelligence to review international students’ social media accounts.

As an administrator and scholar who specializes in international higher education, I know that international students in the United States have long been subjected to a high level of vetting, screening and monitoring.

Inserting additional bureaucracy into current processes could make the U.S. a less attractive study destination. I believe this would ultimately hamper the Trump administration’s ability to achieve its “America First” priorities related to the economy, science and technology, and national security.

In early April 2025, the Trump administration terminated the immigration statuses of thousands of international students listed in a government database, meaning they no longer had legal permission to be in the country. Some students self-deported instead of facing deportation.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security recently announced that it would reverse the terminations after courts across the country determined they did not have merit.

These moves come as the White House seeks to enhance vetting and screening of all foreign nationals.

The State Department in March announced plans to use artificial intelligence to review international students’ social media accounts.

As an administrator and scholar who specializes in international higher education, I know that international students in the United States have long been subjected to a high level of vetting, screening and monitoring.

Inserting additional bureaucracy into current processes could make the U.S. a less attractive study destination. I believe this would ultimately hamper the Trump administration’s ability to achieve its “America First” priorities related to the economy, science and technology, and national security.